How to Improve Your Handwriting

Written on November 27th, 2020 by D. T. Grimes

In grade school, we were told that high school teachers wouldn’t accept papers that weren’t written in cursive. By high school, we learned this was not true. Throughout my young adult life, handwriting became less and less important. Eventually, it served only as the way that I filled out forms at the doctor’s office or signed my credit card receipts.

For years, I’d resolved myself to have bad handwriting. I didn’t believe that I was capable of anything else. Now I know I simply didn’t have the right spark of interest or place to start. This article aims to provide that spark if you are wondering, like I did, how to improve your handwriting as an adult.

Table of Contents

1) Why do I want to improve my handwriting ability?

Not everyone is interested in pursuing professional penmanship. Some just want to have a better signature, while others require professional handwriting for the workplace. I don’t believe that any reason is nobler than the next, but it can be helpful to have an idea of what spurs on your newfound interest. Reflect on that for a moment.

Each of us have different opinions about what good handwriting should look like, while society has its own, collective view. Our writing is often seen by others as a reflection of ourselves, our potential, intelligence, work ethic, etc. It affects what people think about us or the information we use it to convey (Morris 2014). Is this reason enough to invest the effort necessary to improve? I’ll let you be the judge of that.

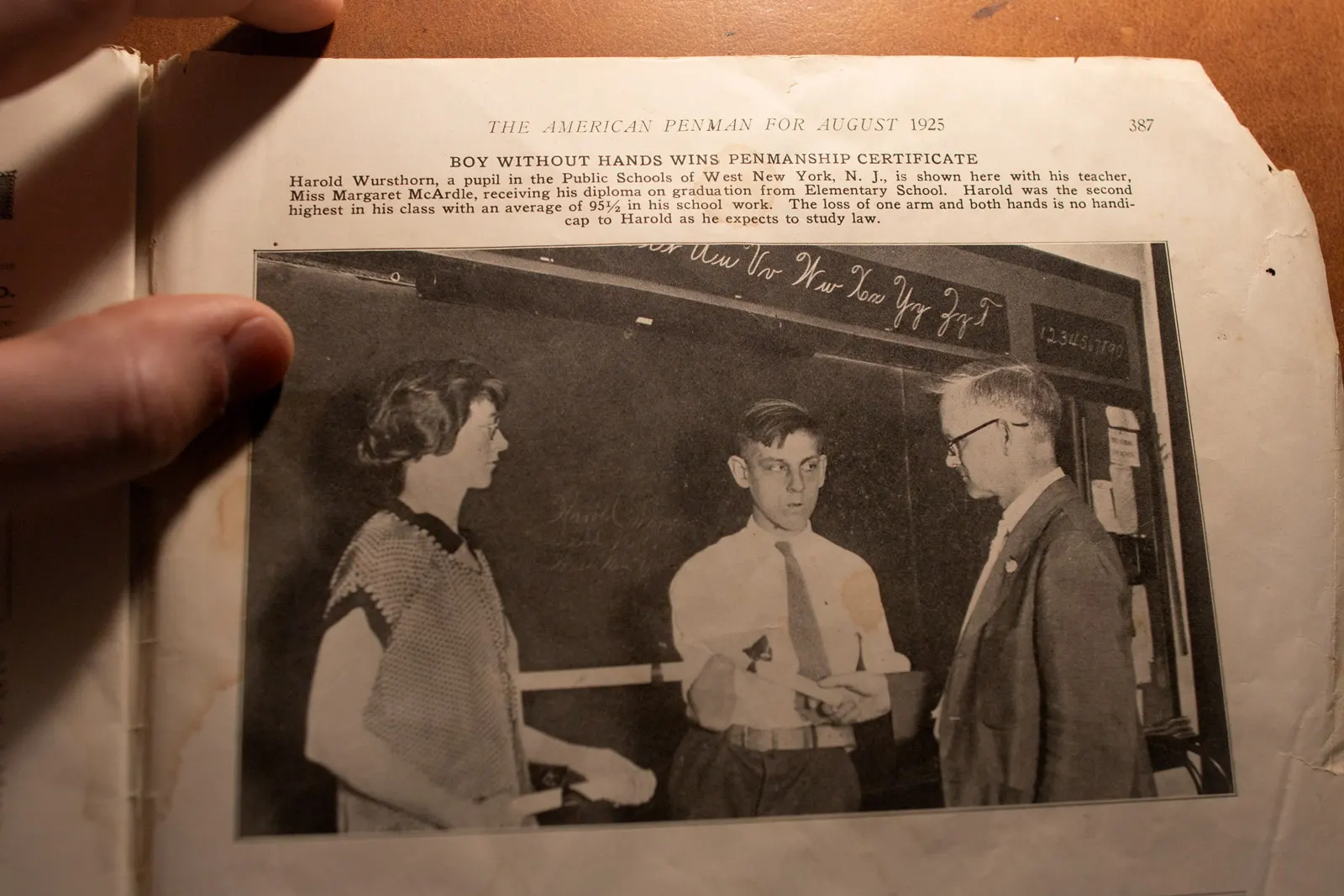

Harold Wursthorn, a young man without hands, wins a penmanship certificate in hopes of studying law. 1925.

2) I know my goal. Where do I start?

As a budding penman, you have some decisions to make. From the tools you use to the method you study, there is a world of possibilities before you. Measure each decision by how it helps you achieve your goals. Consider your effort towards better handwriting akin to a “choose your own adventure” novel. The choices you make provide you with unique experiences that can move you forward towards your goal or distract you from it. Ask questions and be thoughtful. Handwriting is filled with more rabbit holes than most penmen like myself prefer to admit.

A caution: The caveat to this “question everything” lies in the topic of materials. Many students desire to acquire the best pen, paper, and ink under the assumption that better materials equate to better results. While this is true in some circumstances, it’s rarely so in penmanship. Experience, insight, and thorough training are far more valuable than the most popular fountain pen. Practice time under your belt should be your primary desire.

Don’t waste your time looking for shortcuts. There are no surefire ways to achieve true excellence in writing that work every time for every student. Progress is won through hard work, experimentation, and determination.

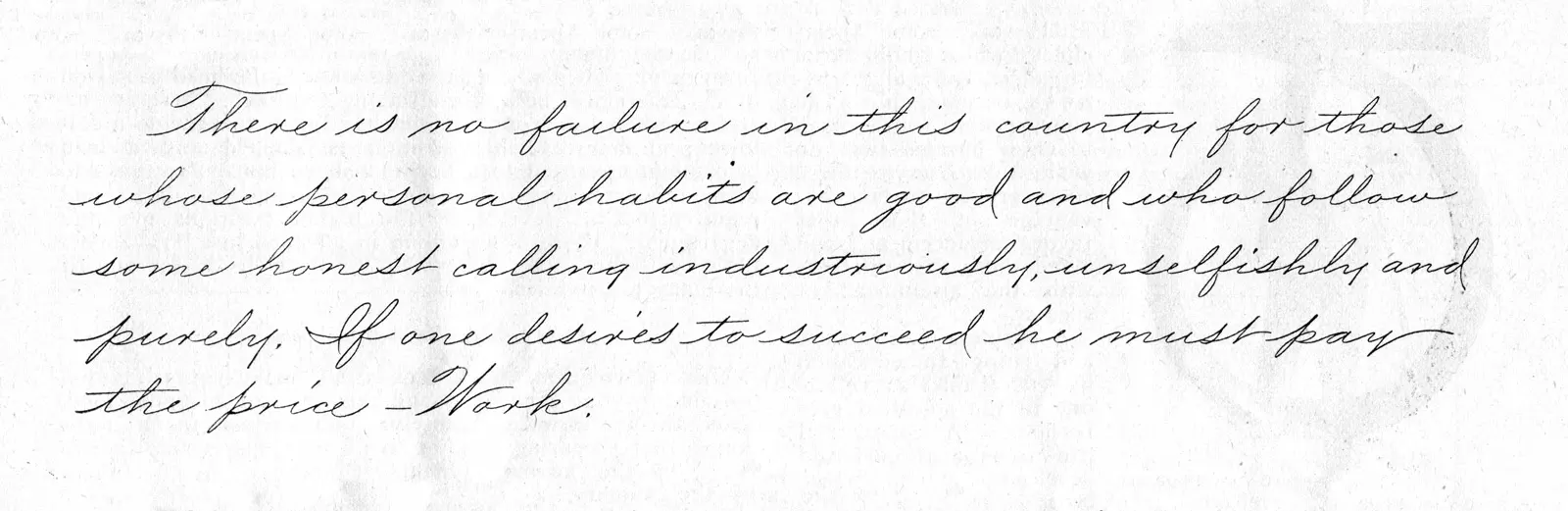

Copies for Body Writing by F. B. Courtney, 1914.

3) What are the characteristics of a good handwriting style?

First of all, “good handwriting” erroneously implies that there’s social consensus as to what makes handwriting legible, aesthetically pleasing, functional, or any other number of desirable qualities. Good handwriting means something different to each of us. Instead of trying to define what specific aesthetic qualities good handwriting should have, let’s focus on ideas and techniques that lead to our handwriting serving us better.

What are the “universal truths” of handwriting that improve its usefulness in communicating with others and recording our thoughts?

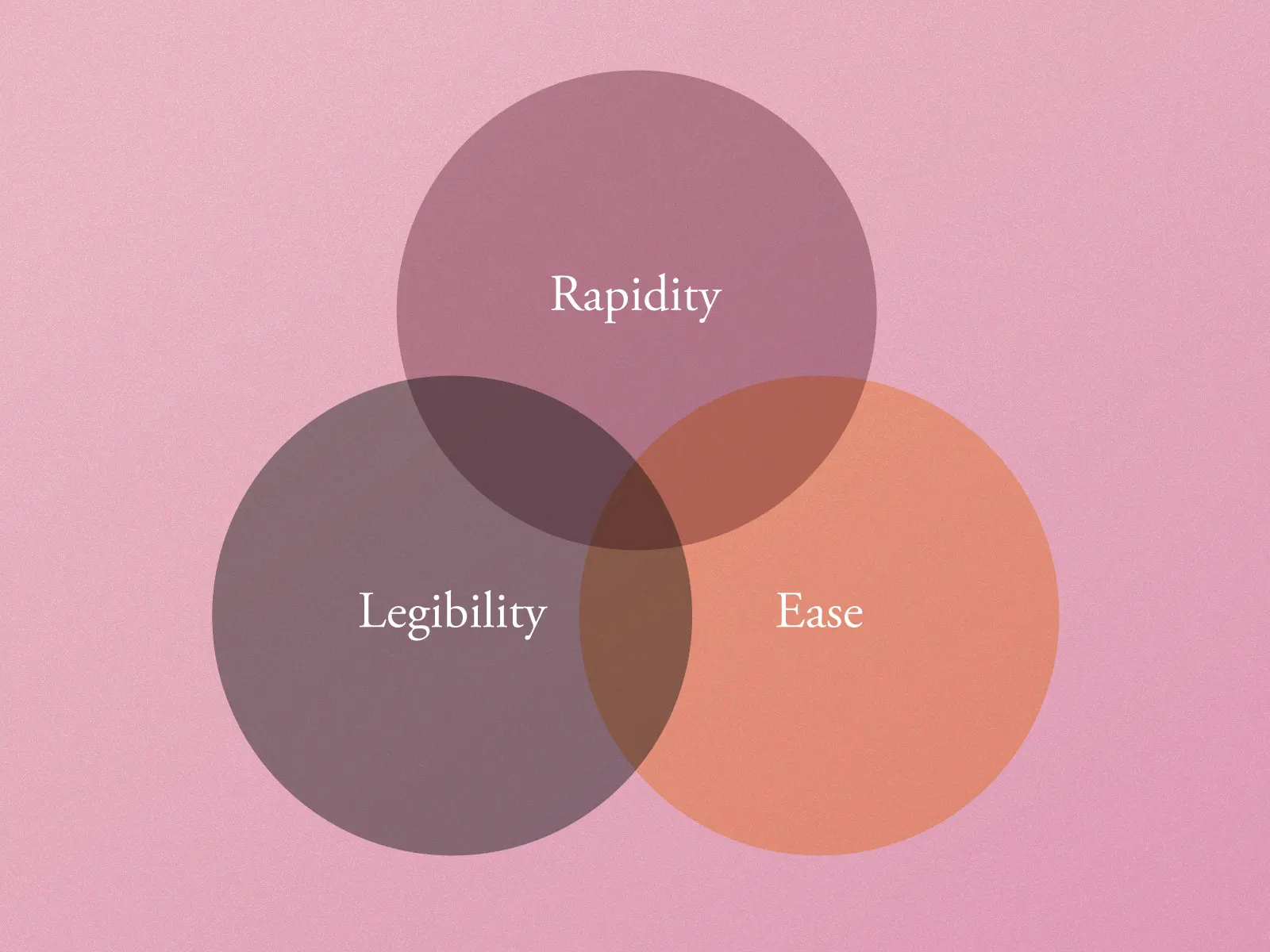

Rapidity, legibility, and ease

A generally accepted trinity of desirable qualities in the penmanship ethos is that of rapidity, legibility, and ease. Writing styles that possess these three qualities are likely considered “good” by the general public. Similar to the old saying about “good, fast, and cheap,” certain styles de-emphasize one of these three aspects in favor of the other two. Some styles may be legible and rapid, but not easy, while are others are easy and rapid, but not legible, etc.

Ideally, we’re able to obtain all three through a methodical approach, untiring effort, and a strong desire to see our handwriting improve.

If you consider your current handwriting ability, you can likely determine which of these three characteristics you are most lacking in. Below, we’ll go through some generalized advice about how to reinforce weak spots in your technique and aid you in your quest to improve. While many of these talking points are relevant for both print and cursive styles, this guide is written with a slighty cursive-centric bias.

3a) Gaining Rapidity

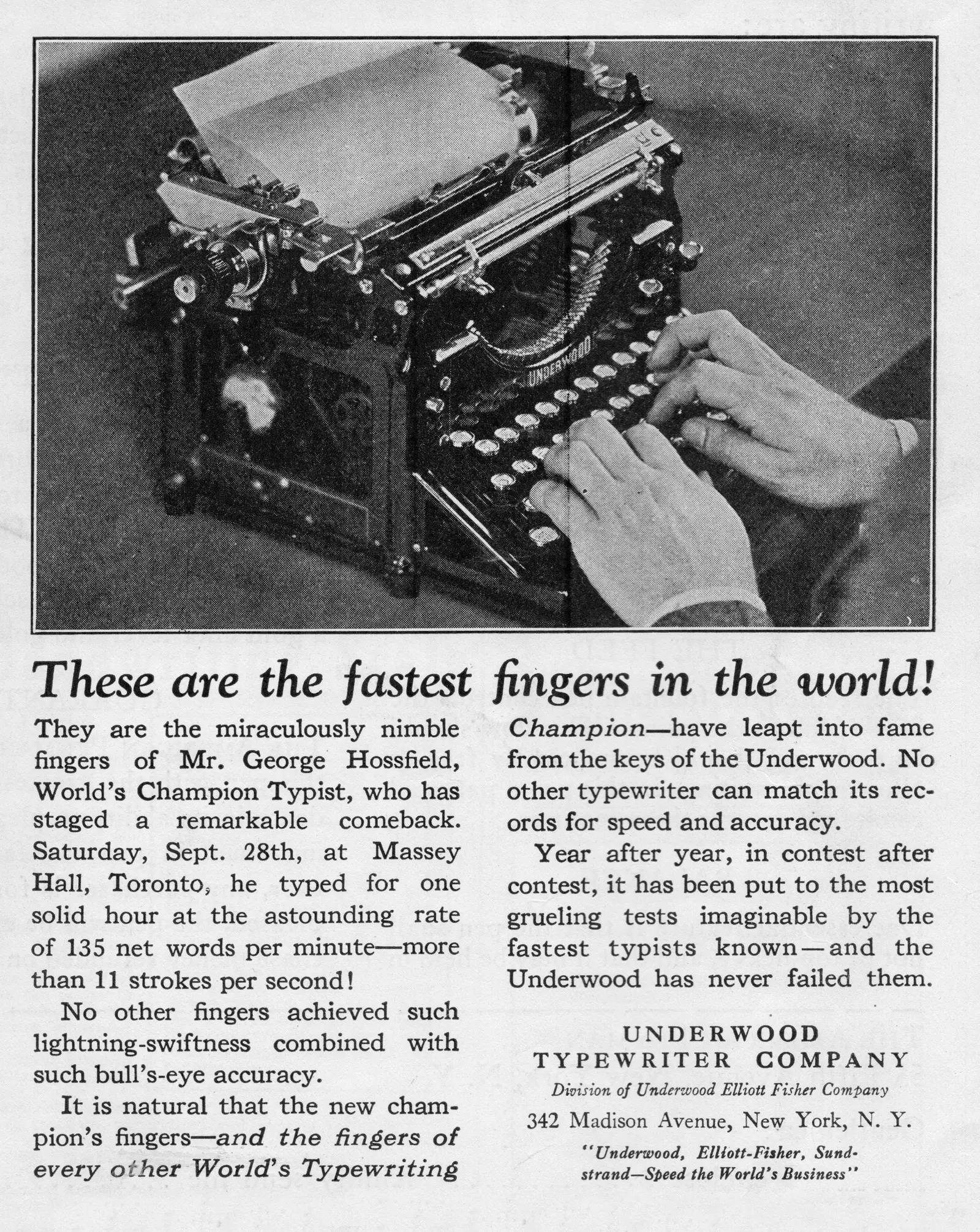

One marker of useful handwriting is that it can be produced rapidly. Humans think and speak at much faster rates than we are capable of handwriting. The average handwriting speed of adults is around 20 words per minute (wpm). Even award-winning typists are only able to achieve slightly over 200 wpm (the average typist clocks in at just around 40wpm). By comparison, the average English-speaker speaks at about 150 wpm, and the average listener can comprehend around 400 wpm.

George Hossfield became the World’s Champion Typist in 1929 with a staggering 135 wpm on the mechanical typewriter shown above. This record has since been broken, but it provides some insight into the necessity of a rapid handwriting, doesn’t it?

If handwriting is meant to be an efficient tool used to record thought, we ought to reduce the discrepancy between our ability to receive information (through listening or thinking) and our ability to encode information into our handwriting. Rapidity should be a factor of all practical handwriting training.

How can I speed up my handwriting?

Certain types of handwriting emphasize smoothness and rhythm as a means of attaining speed. In the case of cursive (from Latin “currere” or, “to run”), the hand typically does not lift from the page, but flows from one letter into the next through what are known as “connective strokes.” The reduction of interruptions and disturbances typically increases the speed at which letters can be formed by the penman.

Over the last century, there has been widespread advocation for a strong, fluid arm movement in handwriting. This movement is driven by the larger, more easily coordinated muscles of the upper arm, shoulder, chest, and back.

These techniques stand in contrast to the typical finger and wrist writing that many children are taught today. Writing with the arm allows for a penman to execute letters using gestures rather than crafting them with individual strokes. By using the gross motor skills associated with larger muscles to drive the stylus, the writer exposes themselves to less strain and increases their endurance and speed greatly.

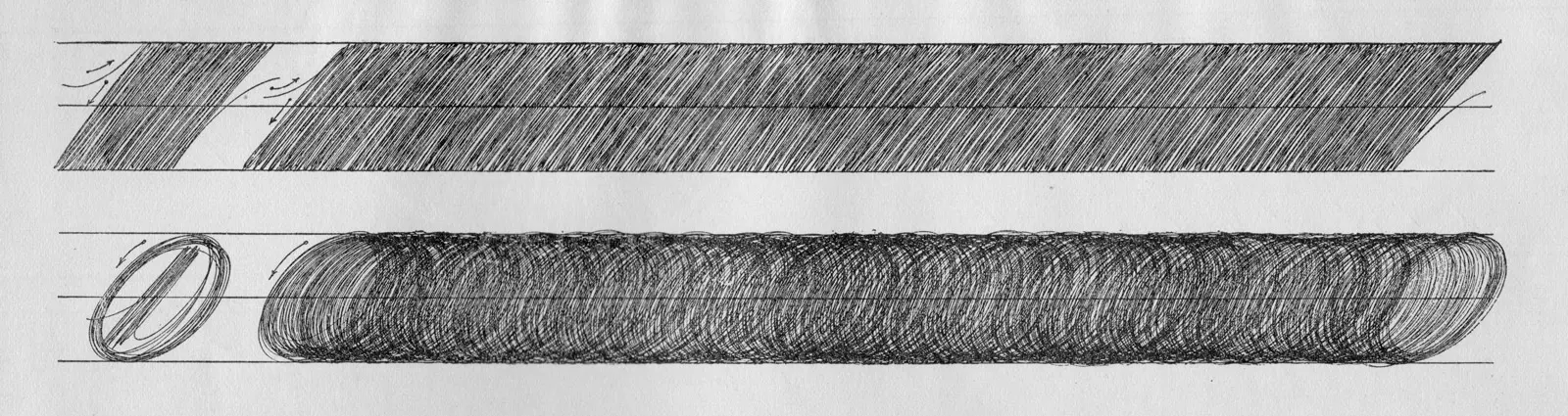

A demonstration of arm movement. Note the elevation of the wrist from the surface of the paper and the lack of movement in the fingers. When using arm movement for writing, the arm oscillates on the muscle of the forearm directly in front of the right elbow.

Observe your own handwriting at a faster-than-usual speed. Do you notice that your movements are emanating from the arm rather than the fingers? If not, how long can you write at a high speed using the fingers, exclusively? To a discerning student, the endurance-based benefit of using the arm should be apparent.

Fluidity as well as speed

When you begin thinking about how to reduce your over-reliance on the fingers in your writing, you’ll often end up stumbling across movement exercises aimed at developing the motor memory necessary for fluid movement. These drills adorn the beginning pages of nearly every practical cursive book from the last century.

Movement Exercises, Edward Mills, 1903

This motor memory is cultivated through regular practice of a gamut of exercises aimed at producing specific patterns to a given tempo. A cursory glance at any number of historic penmanship manuals shows that writers have been thinking about the speed at which the pen should move for hundreds of years—often citing a certain number of “downstrokes” each minute. So too should we, but to what end?

These numbers give us some idea of the speed at which we ought to move the pen across the page, but our best contemporary writers slow down significantly when producing their finest work for educational purposes. This unrealistically careful work is known as a “model” or “copy” hand. As a result, we’re left confused regarding differences between the speeds suggested to develop movement and the optimal speed for both every-day and model writing.

I asked my friend and colleague Michael Gebhart for his thoughts surrounding speed in the context of practice, performance, and demonstrative environments:

“I would only recommend practicing fast writing once legibility and rhythm have been secured. And even then we must be careful to not make a habit of writing fast, but to build up speed methodically by way of dedicated practice and conscious muscle memory training. Most writers will develop speed naturally over time without thinking about it—this kind of rote “practice” will always result in a messy and imprecise pathway towards faster writing. Muscle memory is a powerful thing and has a way of sticking around even against our better judgement. Better to be in control of the habit building from the beginning.” (Gebhart, Message to author, November 25th, 2020)

It is not likely that a certain speed will be best suited for every person attempting to improve their handwriting. Nor do I hope to insinuate that the acquisition of a faster technique should overshadow your pursuits towards increased legibility or belabor the execution of your chosen hand. The importance of speed versus rhythm in Gebhart’s words highlights a critical aspect of developing usable handwriting: it should be methodical, smooth, and easily orchestrated. In turn, this leads to it being fast. In this circumstance, the old swimmer’s adage applies: slow is smooth and smooth is fast.

Our goal should be to achieve as much speed as possible without introducing adverse effects elsewhere in our writing. Illegible writing is nearly useless, no matter how quickly it is produced. A balancing act is required.

3b) Improving Legibility

Of course, it doesn’t matter how quickly we can write if what is written cannot be read. Speed and legibility are often envisioned at opposite ends of a spectrum, but it doesn’t necessarily need to be that way. To some degree, this dichotomy is managed by carefully electing where increased speed comes from, and at what costs (if any) to the tenets of legible writing.

Legibility is a somewhat subjective quality that relies heavily on the familiarity of the reader with the styles and letterforms we select. Readers who were never taught to print may find certain styles difficult to decode, while others may believe that cursive always looks like a pile of spaghetti. Don’t be fooled into thinking that any particular style of handwriting is legible to everyone. Instead, let’s focus again on general concepts that can be used across-the-board to improve legibility.

Legibility is influenced by numerous factors when it comes to handwriting. Endeavor to cultivate these attributes and it will typically improve in the eyes of most people you come into contact with.

Pursue regular and familiar shapes

Reading is a type of pattern recognition. The writer takes information that is within their mind and encodes it upon a piece of paper by utilizing a system of consistently formed shapes to represent phonetic sounds. The reader then recognizes these characters and uses them to access their memory for the sound associated with each letterform and assemble them into words. Legibility influences the speed at which a shape may be seen, recognized, decoded, and stored in memory. The more recognizable a letterform is, the more legible it tends to be.

Maintaining consistent letterforms requires the reader to become accustomed to fewer shapes and allows them to parse the information from handwriting more efficiently as their experience with it increases. Shape idiosyncrasies can be thought of as a writer’s “accent.” As long as a writer is consistent within their own system, the accent soon disappears to the reader. It is only when a new letterform is introduced that the reader is forced to recognize the writer’s accent again, which can be distracting and therefore harmful to legibility.

Apricots, by Sophie Louisnard. I’d have taken my own photo, but it turns out apricots are a summer fruit so I couldn’t find any locally. Typical.

For example, there are two common ways to pronounce the word “apricot.” The first is to use the long a “ape-ri-cot,” and the second is to use the short a “app-ruh-cot.” Both pronunciations are generally considered correct and relate to the same idea, but depending on which version you grew up with, an extra step of translation might be required before you can conjure forth in your mind a small stone fruit. Think back to the last time you heard someone say a word like “apricot” using a pronunciation that you don’t use yourself. Isn’t it jarring when a word doesn’t work as efficiently it’s supposed to?

This cognitive lag when a reader is trying to determine what type of letter they’re reading is something to be avoided in practical handwriting. By reducing the differences between each instance of the forms used in your handwriting, you are decreasing the effort it takes for readers to decode it.

This also applies to what are considered standard forms, or those typically understood as standard models by the general public. If you employ an unconventional variation of the letter “p,” the reader might still struggle to understand your script even if you are mechanically consistent with all of the other unconventional “p’s” you use on the page. Try to show the reader something they expect, and your legibility will increase dramatically.

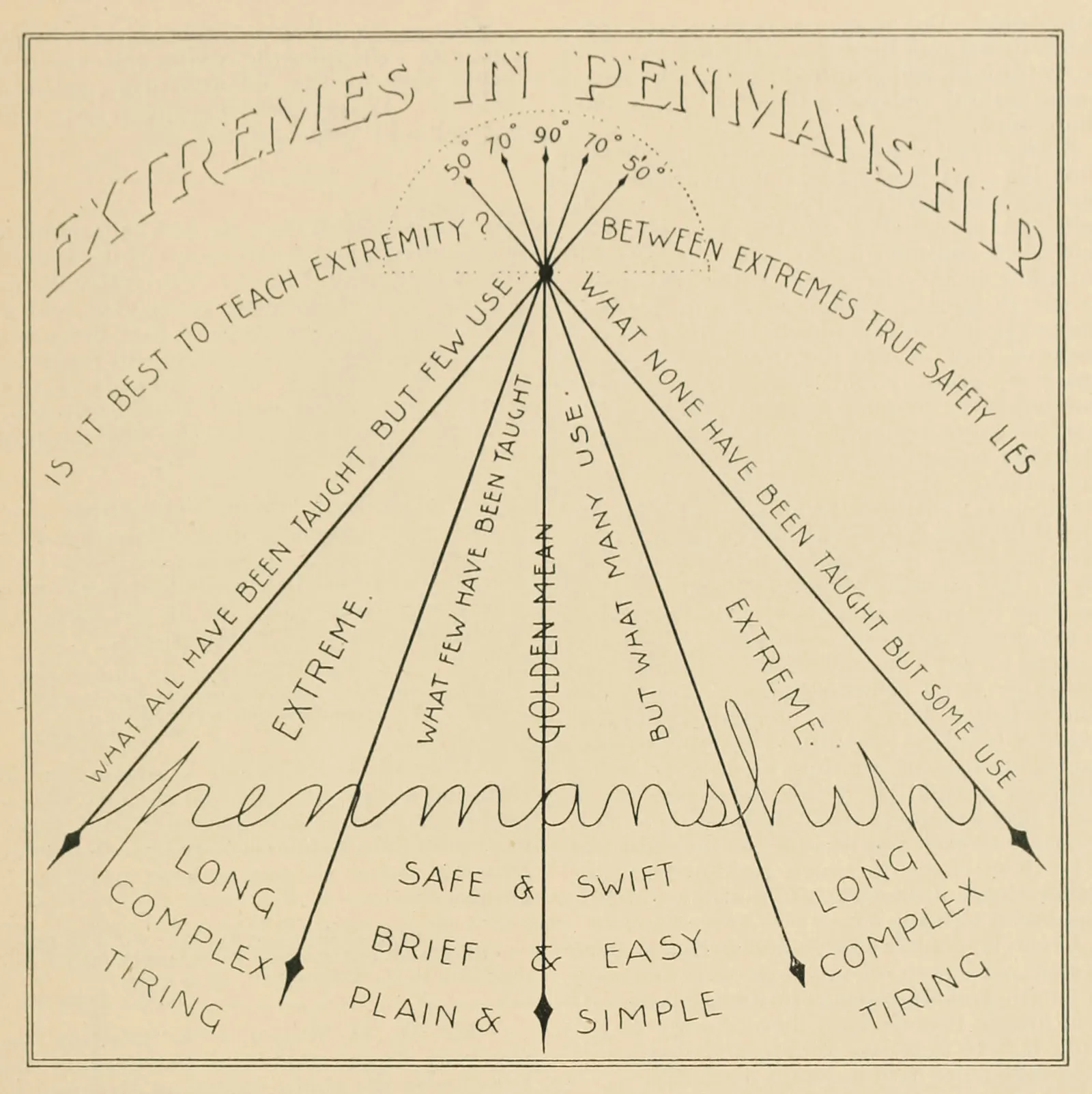

Maintain a consistent slant

There are numerous acceptable slants in writing. It’s been debated by professional penmen for almost a century that one slant is more acceptable to teach children, or for business use, or faster than another. The truth is that each slant has its own benefits and aesthetic qualities. Deciding the right slant for you is a question best asked with a bit of experience under your belt, so don’t be too keen to settle on one slant right now. Experience is the best teacher in this regard.

Whatever slant you choose, make it regular. Aim to keep all of the downstrokes in each of your letterforms as close to the slant as possible. Doing so will give your writing a uniform appearance that does not tire the eyes of the reader. One good tip to evaluate your own work is to take a page of your writing and hold it up to your eye so that you can look across the surface from the lower-corner along whatever slant you choose. From this angle, you will be able to see where you are off of your slant in the same way a carpenter determines if a board is crooked.

The easiest way to manage slant is to rotate the paper so that all downstrokes are pulled directly towards the center of your chest. For a typical right-handed writer, this would mean that while writing vertically, the baseline is parallel to the edge of the table. While writing forward-leaning script the paper should be rotated so that the baseline departs from the writer to the right. For a backslant style, the orientation should be the opposite.

Extremes should be avoided. There is a safe zone inclined to the right and left of vertical where writing’s legibility is not affected negatively by the chosen slant of the writer. Too much in either direction, however, and the work becomes condensed and difficult to read.

Extremes in Penmanship. A provoking graphic by Charles Zaner. 1896.

Develop even spacing

Similar to the way our eyes recognize consistent shapes within our letterforms, the space found between one letter and the next controls the rhythm and legibility of our handwriting. By considering the white space between letters, we can abstract our handwriting to be black marks dividing up white spaces. Doing so makes it a bit easier to understand the importance of careful spacing. Imagine the even spacing of a white picket fence. You wouldn’t want to build a fence with uneven slats would you?

The distance that letters, words, and lines are placed apart from one another has a lot to do with the effort required to read handwriting. Take care to make sure that you evenly distribute the letters within your words and watch out for tricky letters that might need a bit more or less space than usual. Do your best to make sure that lines are spaced widely enough that your ascenders and descenders (such as “l” or “j”) do not conflict with one another. Remain vigilant for scenarios where momentum might carry your pen between forms excitedly at the cost of the appropriate amount of lateral space.

One strength of cursive is that the letters tend to only be separated from one word to the next. In instances where poor spacing is applied, readers still have a good chance of corretly determining which word a group of letters belongs to. In print styles, lateral spacing errors can be more catastrophic as the reader must determine which word a letter belongs to.

3c) Keeping it Easy

A final hallmark of a good handwriting style is that it does not require a magnificent effort to create. Certain types of calligraphy are laborious to assemble into writing. While beautiful, these styles of lettering should be avoided where utility is concerned.

Good, easy handwriting requires less strain on the body to produce and can be sustained for a longer period of time without needing to rest. Proponents of arm movement declare that using larger muscles like those in the shoulder, chest, and back can help to alleviate the strain placed on the smaller muscles of the fingers, wrist, and forearm reducing what is commonly known as “writer’s cramp.”

Proper posture, position, lighting, and the development of smooth movement allow the writer to produce letters with ease. In turn, more mental energy is reserved to direct towards legibility and speed. An easy handwriting style is one that is not in the way. It may seem obvious, but sometimes the best solution to cramped, untidy, difficult handwriting is to make it simple and try to relax.

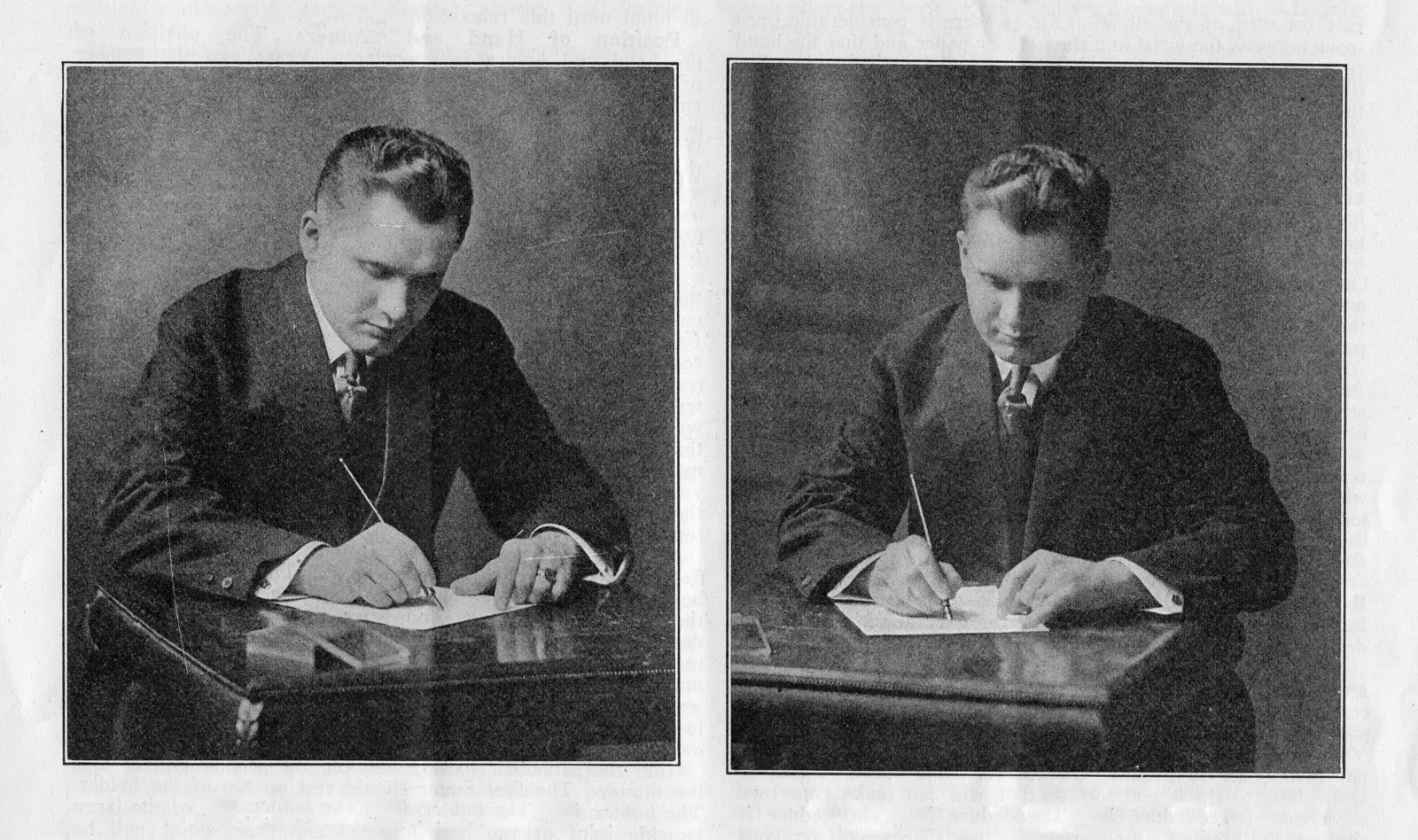

Penman W. R. Stolte of the Commercial High School, Providence, RI, demonstrates the correct position for business writing. How does yours compare?

“The first important problem to be considered in learning to write is the development of a natural, healthful position…it will be observed that muscular relaxation is absolutely necessary and is acquired only through a natural position. A natural writing position is one which is suited to your individual case. This is found to be logical when you observe how persons differ in size and weight. We could hardly expect, and it would be useless to advocate, the same position from a rather corpulent fellow and one of the “bean pole” type…” (Stolte 1927).

Simplifying your writing can be accomplished by a number of methods. The easiest way is to audit the forms you use and look for places where you can reduce their complexity without decreasing their recognizability. Small details like serifs and tails can often be skipped altogether. Experiment and explore.

What type of writing feels the easiest to you will depend on many different personal, subjective factors. Similar to how a fast, illegible style is useless, a style that you do not enjoy writing or reading due to its over-simplification or sterile aesthetic is unlikely to be one that you spend the effort to cultivate. Find something that you like the look of, that you can systematize, and that takes no great strain on you to create.

Conclusion

I hope that this guide has helped you understand how to improve your handwriting. Whatever style of writing you choose to pursue, establish clear goals early on and you’ll be well poised to tackle your handwriting improvement methodically and efficiently. Through continuous assessment of your handwriting against the tenets of rapidiy, legibility, and ease, you can strategically approach your practice in an informed and productive manner.

All progress in writing is made in single strokes. As your life has been made up of individual days, each stroke adds its strength to the legion penned before it, developing you slowly but surely into the penman you hope to become.

D. T. Grimes

Questions? Criticisms? Feel free to reach out.

References

- Gesell, Arnold L. 1906. “Accuracy in Handwriting, as Related to School Intelligence and Sex.” The American Journal of Psychology. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1412252

- Morris, Kathryn J. 2014. “Does Paper Presentation Affect Grading: Examining the Possible Educational Repercussions of the Quality of Student Penmanship” Honors Theses, Salem State University. https://digitalcommons.salemstate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1025&context=honors_theses

- Stolte, W. R. “Department of Business Writing.” The American Penman, February, (1927): 166.

Updated Jan 15th, 2025.