The Specialist’s Dilemma

Written on March 12th, 2022 by D. T. Grimes

Specialty is an confusing phenomenon. It’s commonly accepted that specializing in a niche field increases the quality of the contributions that an an individual can make. However, the concept of specializing—particularly when it comes to penmanship—is often seen as being at the expense of other knowledge and abilities. A specialist might excel in one avenue of script but flounder in others. One common thought is that there’s a certain sense of perspective that one loses by focusing on the specific, rather than the general. Western culture glorifies “renaissance men” who are capable of a wide range of feats, but overlooks—or even admonishes—specialists until we have a need for them.

I see nobility in the pursuit of that which might not be cared about by others. What drives someone to become a cork maker? Surely the corks that top our bottles of wine must come from somewhere? They don’t just grow on trees, do they? (they do!) The world is filled with curious oddities and overlooked details that are the products of specialists. So, what’s wrong with being one? Don’t we need specialists?

“A human being should be able to change a diaper, plan an invasion, butcher a hog, conn a ship, design a building, write a sonnet, balance accounts, build a wall, set a bone, comfort the dying, take orders, give orders, cooperate, act alone, solve equations, analyze a new problem, pitch manure, program a computer, cook a tasty meal, fight efficiently, die gallantly. Specialization is for insects.”

— Robert Heinlein, 1973

This quote is designed to conjure forth some sense of the holistic man—a good man. It implies that humans should be self-sufficient. That we should be capable of doing everything that needs to be done. Extrapolating that a step further, we might even assume that it means we should not rely on others. Maybe, even, that they aren’t dependable. The only competency we can always count on is our own.

But I didn’t get into calligraphy to be stuck on a deserted island. I wanted to connect with people—to communicate with and inspire them. I wanted to help them think about what they could do with their lives besides sitting around taking crap from their boss or lamenting the town they were stuck in. I wanted to be proud of what I was doing with my life, and share that with my friends. To do that, I needed to be good at something.

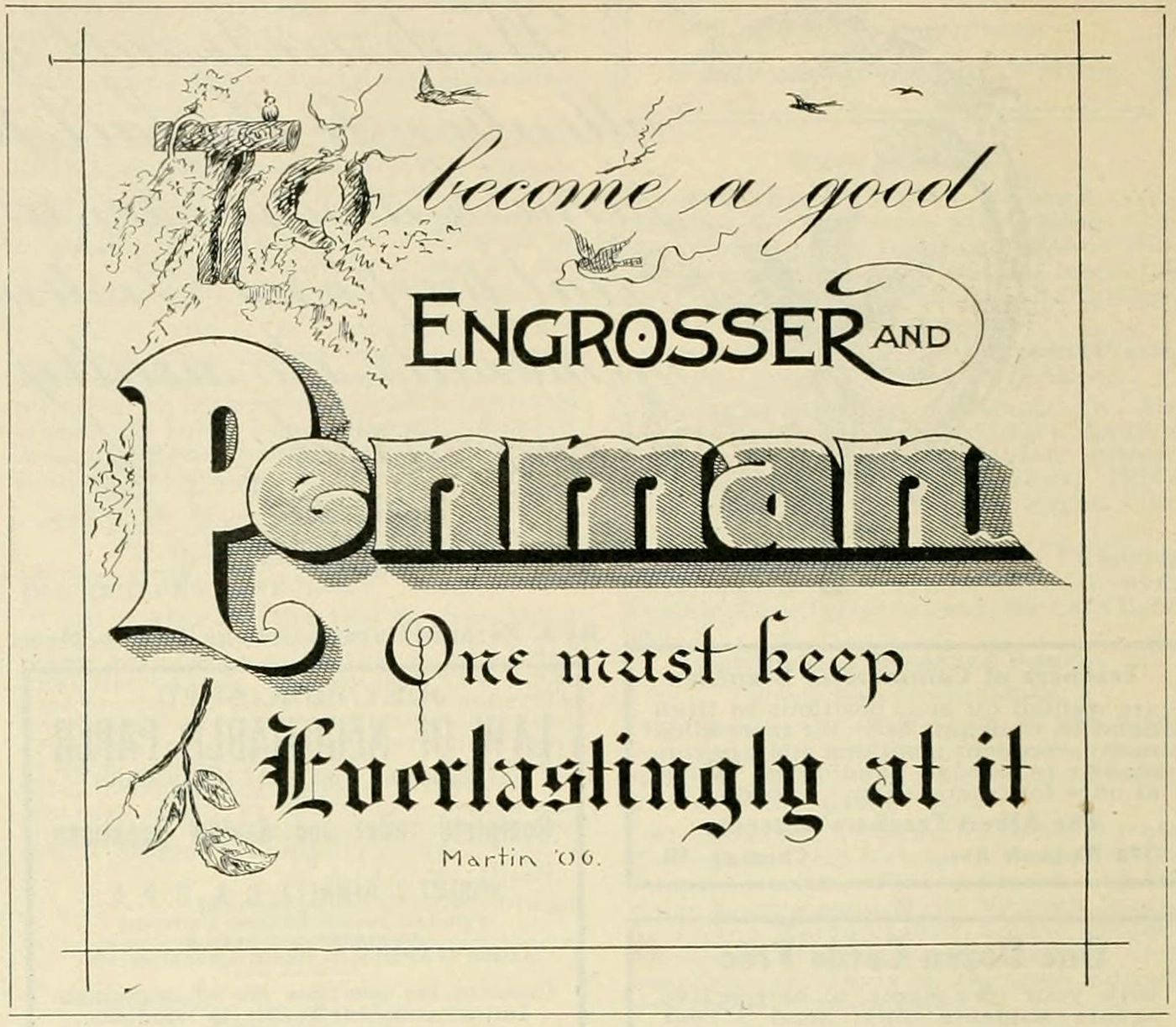

Engrosser’s Script presented itself as a natural challenge to me. At the time, there were only a few resources available that could get someone like myself moving in the right direction. (Thank you, Dr. Joe Vitolo—I’ll forever be in your debt.) What I couldn’t learn from a book I had to dig up in a century-old magazine or stumble upon by chance while practicing. Engrosser’s Script was rewardingly hard because it was specific. It seemed like the honorable thing to do was to repay it with my full attention.

From that experience, I feel justified in claiming that getting to a point of specialty in a script takes a large amount of effort and focus. By spreading ourselves out so that we can fulfill every aspect of the calligraphic process, we might overlook the details that are required to produce work that reflects the craft our specific script deserves. Do we owe it to ourselves to be the best penmen that we are able to be? I suppose that depends on our motivations. I’ve certainly feel that I do.

Yet, over the years, I’ve had other calligraphic interests besides Engrosser’s Script. I didn’t necessarily identify with them in the same way, but they all aided me in my quest. The most important thing I gleaned from my studies was the connectivity between scripts. The lessons learned through the practice of one might not translate to another as far as the pen is concerned, but the concepts and ideals certainly contribute to a stronger underlying calligraphic foundation. By focusing on the whole, I was reinforcing the specific.

Through generality, I sought tempered expertise.

Expertise is supremely useful; it instigates collaboration between those who possess it. How many times have I referred to another penman for advice in an area other than Engrosser’s Script? I’ve found great joy visiting the study of my friend Holly who teaches me about illumination techniques she learned from her father—A Zanerian penman. Inside that friendship, our expertise brings us together more often than if we were both generally competent in the same things. By considering myself a novice in some areas and an expert in others, I’m continuously pulled between being a student and a teacher. What a rewarding way to experience calligraphy! To give and to get. Balance.

Perhaps insisting on one box or another (specialist or generalist) is a reductionistic view of the reality of being a 21st century calligrapher. The world does not rely on handwriting for communication anymore. We do not need clerks and secretaries to record business transactions and letters of commerce. We write because we enjoy it, or we enjoy the look of it. It’s no longer about the utility of our writing, but about the artistry in it.

One does not need to forsake the whole of lettering for one specific script, nor avoid being drawn into the details of something for fear of losing skill in others. The natural path is to follow your interest, work hard, and dig deep into what you find yourself enjoying each moment. When that interest changes, so can the categorization of our practice.

I suppose, then, that I should reframe my self-image of possessing a specialty in Engrosser’s Script. Instead, let’s say that I retain a deep interest and satisfaction in having some expertise to offer to my community and colleagues, while fostering a healthy curiosity of the other aspects of calligraphy that surround it. I do not wish to be known as a one-trick-pony, nor a jack-of-all-trades. I am somewhere in-between, like so many things in calligraphy: a revolving door of experiences and motivations. A specialist one moment and a generalist the next. How that appears on the outside is simply a matter of the reader’s perspective.